Time presses us to move to Odysseus and Telemachus before we alight on the next father-son pair, God and Christ.

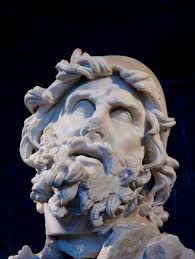

Odysseus, Auerbach summarizes, is a great man, a warrior; Homer deigns to write only of great characters. The Antique Greeks wrote in two different styles: high for great characters; low for the hoi palloi (Auerbach). For the Greeks, character is etched (as the word translates), engraved in our bones so that we are recognized wherever we turn.# Both character (eidos) and persona are words of Greek origin: persona is the mask that actors wear to portray different roles; character is what remains consistent in all settings. Just as each letter is a character to distinguish it clearly from another, so too, man. (This distinction between persona and character may be a vorspeisse of false social self versus true self.) Odysseus is cunning, crafty from beginning to end. Remarkably, Auerbach says, Odysseus over two decades’ voyage does not change. He leaves his one month son, Telemachus and his dedicated Penelope, who fends off suitors/squatters. After twenty years, let’s turn to Odysseus’ disguised return to meet his son Telemachus.

First, as if to prepare us, we hear of Odysseus meeting Eumaeus, his trusty, dedicated swineherd who does not recognize the Athena-altered old man. How does this representation of reality differ from Bible? Listen to the details of Eumaeus’s cottage and swine styes:

...built by himself… with stones from the quarry.. and coped it with a fence of white thorn and he had split an oak to the dark core and…driven stakes the whole length thereof.. and within the courtyard he made twelve styes hard by one another to be beds for the swine and in each stye, fifty grovelling swine.. but the boars slept outside.” (Book XVI).

How visual; how sensual, how different than Bible.

Then, father sees son, who doesn’t recognize him. Even after Odysseus says, “I am your father, for whose sake you suffered many pains and groans and were submitted to men’s spite,” even after he kisses him and sheds a single tear, Telemachus believes some god deceives him. Finally, he flings himself on father’s neck and “…they wailed aloud, more carelessly than birds, sea-eagles or vultures of crooked claws whose fledgling young the country folk have taken from the nest…” They would have cried all night, Homer tells us, but Odysseus gets to the matter at hand: massacre Penelope’s suitors. Athena insists Odysseus must first make blood before he can make love. This goddess has priorities.

The next episode tells us more of Odysseus character. Again, too briefly, Odysseus, disguised as a beggar enters his old home. Unwitting Penelope greets him and asks Euryklea, his former nursemaid, to wash this stranger’s feet. Odysseus, realizes that Euryklea will recognize the scar on his thigh; he claps one hand on her mouth, the other on her throat and whispers roughly, reveal my identity, and I will throttle you. A decisive man, even ruthless.

Auerbach places these texts side-by-side to understand their Weltanschauungen. The Bible’s narrative is spare, we see the moment, foreground; we know little of what characters think or surrounds them. All is shot with a shallow lens. Abraham takes Isaac hiking three days to sacrifice him; no word is spoken until the foot of the mountain. Jacob calls Joseph to send on a lengthy journey; Joseph answers Hineini, that fateful, single Biblical word, “Here I am,” a word that portends something unknown, powerful and likely dangerous. One God they possess; a God both feared and yet turned to for protection … or at least justice. Intimacies are charged: Joseph’s brothers hate him unto death; Jacob adores him; his mother is dead. Family, a people-to-be, possibly a nation, is foremost in Jacob’s and Joseph’s minds. Jacob’s women — four — clamber upon him; for Joseph, one is briefly mentioned. Names carry meaning: Jacob — either “ankle-grabber” or “crooked one.” Joseph, “and God will add (another son).”

Homer’s characters are voluble. What they think, they tell; where they are, Homer says. How did Odysseus get scarred some forty years earlier? Odysseus/Homer flashes back, his hand hard upon Euryklea’s throat. And Homer speaks of great characters, no rifraff rabble, no vulgus here: we hear of gods or demi-gods, not shepherds or tent dwellers. Names carry meaning: “Odysseus” is “one who is wrathful/hated”; “Telemachus,” “far from battle.” Odysseus is admired for his cunning and deceit. And Gods — battling, petty, impregnating, form-shifting — reign Odysseus’ life, with one his guardian, a beautiful goddess of war. Intimacies are limited: all Odysseus’ men die; he yearns for his dedicated wife, but is “fooled” by bewitching Calypso, stays with her seven years, believing that it is but seven days, a (self-) deception clever Odysseus would like his listeners to believe.

In both texts, names carry meaning. Names condense. They concentrate “unconscious ideas and images of self hood,”# place in family and identities. These identities are imposed upon us and often accepted or rejected, such as in Moby Dick’s protagonist, who begins, “Call me Ishmael.” We never learn his given name; only that his assumed name is of a son sent out by his father to die; instead, this young man, survives as he searches for an identity. But, Joseph ultimately becomes his name: while he was named “to add” pointing to his brother to come; in adulthood he adds to, enriches the lives of others.