“Begin at the Beginning and end…”

“The End is in the Beginning”

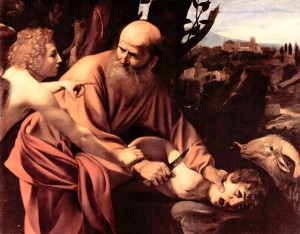

Let us begin with Bible and Homer, with a meeting of father and son. Auerbach compares the Abraham-Isaac Akeda, the binding, to Odysseus meeting Telemechus after two decades absence. Here, I compare the Jacob-Joseph meeting after two decades with Odysseus-Telemechus and the relatedness between the father and son. I suggest several reasons to select Jacob and Joseph rather than the more notorious Abraham – Isaac story.# I suggest that the Jacob-Joseph story is the foundational myth of father-son relatedness that permitted an enduring Judaism. Further, we know so little about Isaac; he falls silent after his near sacrifice; speaks only until after his father’s (and mother’s) death.#

Of Jacob and Joseph we know more than earlier Biblical characters, a lot for the laconic Bible, a book that Auerbach says — unlike the Iliad and Odyssey — gives little background, much foreground and hence presses for hermeneutic interpretation. Homer and his characters are voluble, tell us what they think, flash back into histories. Of Bible, we have a desert of description, succinctness of acts or words, descriptive aridity. Following Auerbach, after we touch on Bible, we turn to Homer.

The father Jacob is notorious. Battling his twin in the womb, later described as a tent dweller unlike his hunter brother, he soon bests his brother, plots against his father with mother’s collusion and is on the lam from his brother for two decades. His name, “Jacob” is a pointing name: “heel grabber,” as it points to his brother who preceded him in birth. Later, deceived by his uncle/father-in-law, whom he deceives in return, Jacob escapes home with two wives, two concubines, twelve sons and a daughter and wealth. After battling God’s angel, he is renamed Yisrael# — “God-battler” — he goes through other travails including losing his favored son, Joseph (unbeknownst to Jacob, because of his envious sons).

Slide 3: Joseph

Joseph’s name also points, but to the future: “God will add,” his beloved brother, Benjamin, their mother dying in childbirth. The favored Joseph proudly (or naively) announces his dreams of succession, of rule, unaware of the envy he generates in his brothers, although his father reproves him after misinterpreting the second dream. Father misses the wish embedded in the dream: that Joseph dreams his mother alive. Joseph, sent by his father to spy on his brothers’ industriousness, is cast by them into a pit while they plan his murder, then is saved by one brother, who sells him into slavery (to the offspring of Ishmael, Abraham’s exiled son). I course through this rapidly. But from Joseph’s descent into the pit and his later Egyptian pit-imprisonment, emerges a different man. This reborn Joseph shows evidence of an ego ideal, the first such evidence of this psychic structure in the Bible. I refer to the more creative , super ego-softening aspects of the ego ideal (Chassguet-Smirgel and later Giovacchini), the agency that works for Freud’s object “loved rather than dread(ed).”(Laplanche and Pontalis, p. 145).

Here are the details in brief. Joseph enriches Pharoah, becomes vizier, then meets his brothers who come to beg for food and don’t recognize him. Joseph breaks into a crescendo of crying episodes. His fifth outburst, as he reveals himself, is heard throughout the Egyptian court. Then a final unabashed sobbing breakdown when he meets his father, Jacob, after twenty years: he collapses on his father’s shoulders. Jacob’s response? “Now that I have seen your face, I can go to my grave.” When Jacob dies, his brothers expect Joseph’s retribution for how they wronged him. Instead, Joseph insists that he will provide for them and their children and children’s children. The brothers expect that Joseph’s psychic structure restrains retaliative aggression only out of father-fear; instead, Joseph shows internalized controls, which are not only superego, but also ego ideal. Ironically, even poetically, Joseph “fulfills” his first dream of his brothers as sheaves of wheat bowing to his sheaf, but with a reversal: he “feeds” those circling him.

In short, a father, Jacob, is promised a nation. But, his son, Joseph, fulfills this dream; a son who curbs his impulses,# won’t deceive, won’t retaliate: one who shows a new psychic structure. The son is not murderous towards his father (unlike Oedipus), nor is this father murderous towards the son# (unlike Abraham or Laius … or Christ’s God); Jacob shows no ambivalence about his son’s successes. Most significantly, Joseph changes internally. He is the first Biblical figure who does not speak with God; yet he accepts a unitary god, which psychoanalysts might consider as accepting an integrated self, rather than the multiple gods who run rampant in Greek myth (or multiple part-objects or unintegrated impulses in our inner lives). See how this contrasts with Odysseus. Unlike Abraham-Isaac or Laius-Oedipus, the Jacob-Joseph pair is a more solid foundation upon which to build an enduring society: one in which a father’s dreams can be realized by his son without murderousness nor envy nor ambivalence on either party. We might consider a Joseph-complex rather than Oedipal as a model to explain part of Judaism’s endurance.