Here are several of the notable themes and innovative techniques6 that Caravaggio used to pull the viewer into the frame and to portray emotions in complex manners.

1. His subject matter (given – and despite — the Church’s dictates) pushes the edge of more honest human portrayal, including the prevalence of decay and death: David and Goliath, Judith and Holofernes, Abraham and Isaac, Medusa, St. John the Baptist on multiple occasions, an ailing Baccus with a fixed smile and multiple portrayals of Christ, often with varying facial features. Often, one character plays against another. Even in single portraits, such as his representations of St. John (in some cases, louchely smiling), the figure plays against the observer (including the Church’s elders, we might speculate).

2. Complexity of emotions in the presence of others. In Caravaggio’s hands, the characters portrayed perform like members of a small chamber orchestra: each one’s emotions playing responsively in harmony or disharmony with others’: the emotions evoked by the picture are amplified by the play of emotions among the performers. In Judith and Holoferenes, Caravaggio captures the moment when the Jewish widow severs the marauding General’s head, after seducing him. The physically imposing Holoferenes has mouth agape as if howling, his eyes roll upwards showing shock, perhaps disbelief, even as his left hand grabs the bed linen and the other strains mightily – forearm muscles and triceps bulging, blood vessels distended — to push himself away from this deathbed, or his death. Yet, Judith’s expression is almost passive, her eyebrows knitted in effort. In contrast to Holofernes’ bulging muscles, her left hand softly grasps a tuft of Holofernes’ hair as her right, with unmuscled forearm, completes amputating the head with a scimitar, Holofernes’ blood gushing out towards the viewer’s lap. Her elderly handmaid rushes in with a bag to grab the soon-to-be liberated head, her face fixed in fury, possibly touched with contempt. The triangular interplay of the three characters’ emotions amplifies and humanizes the scene’s power.

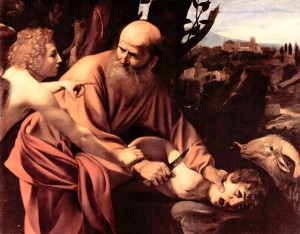

3. In the Akeda, Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac prevented by an Angel, the aged, bald, yet powerful, determined Abraham is poised with left hand pressing Isaac’s face downward, the father’s thumb imprinting the lad’s cheek, distorting the boy’s face. Abraham’s knife-grasping right hand is poised, neckward bound, yet painted as if it were already slicing the boy’s arm. Abraham’s face is turned away from the boy, looking back at the Angel; the father’s brow is wrinkled, his eyebrows knit with a look of determination or anger, or both.7 Isaac’s mouth is asymmetrically open as if shouting, eyes wide-open, his face shows pain anticipated or beginning. The Angel’s face shows no emotion, looking past Abraham in the direction of the ram. Look more closely: a peculiar ambiguity shows between the Angel’s two hands: his right finger points (softly) past Abraham’s chest towards the ram, but his right grabs Abraham’s knife-wielding wrist so firmly that the ancient man’s wrist is wrinkled from pressure. But, the direction of Abraham’s wrinkled skin appears as if the Angel is forcing the father’s arm downward, forcing the knife to its first victim. That is, if we believe that this expert technician, Caravaggio, painted with intent, with precision, then the Angel “shows” ambivalence between his two hands: one directs Abraham’s gaze outward, the other presses the father’s arm towards the son’s neck. In case the observer were uncertain about the Angel’s pressing right arm’s intent, the artist displays bulging forearm extensors and triceps in extension (rather than showing the biceps and flexors, if he were pulling Abraham’s knife away). In an unusual touch for Caravaggio, in the upper right corner – above Isaac and the ram’s head – is a glimpse of landscape.8 But, the remainder of the background is darkly shaded, forcing the scene into our faces.

4. Death and Decay amidst life are central themes threading through Caravaggio’s life work, beginning with his earliest still life (the French, nature morte, a more fitting term) of a fruit basket. While death had been visually portrayed in religious art — notably the passion of Christ or martyrdoms, or of assorted saints – Caravaggio begins to humanize (even secularize) the study of decay and death. His lush nature morte of a woven basket with fruit at closer study reveals overripe fruit: some verge on decay, a spotted apple possibly worm eaten. Caravaggio carries this overripe fruit basket into later works, particularly his portrayal of Christ’s appearance at the home of Emmaus after rising from the dead. Here, the same basket is perched almost precariously over the front edge of the table, towards the viewer almost protruding out of the picture, vulnerable to a fall.9 In this Emmaus (he painted another), a powerful moment is captured: the disciples recognize Christ as he — face impassive – raises his hand to bless the bread. One disciple’s face is clear: shock and surprise; the other, back to us, tensely grasps his chair arms as he is caught mid-leap from his seat, elbow revealing torn fabric. That is, Caravaggio uses not only face to reveal emotion, but also body tension and “movement.”

5. Caravaggio sculpts the peaks and crevasses of darkness and light to focus our attention. First, Caravaggio often uses dark, muted tones – browns and blacks – in the background, pushing the figures into the viewer’s face. They crowd into our attention. Caravaggio plays with light and shadow to focus us on a scene. Early in his work, light comes off-screen from the left, usually upper left, without obvious source. X-ray study shows in one case that Caravaggio painted over the sources of light (a window, a moon). One notable exception is his portrayal of Judas’ kiss and betrayal of Christ. Here the weak light source comes from the right – a dim lamp held aloft by a familiar observer looking in quiet wonder: the painter Caravaggio, a Zelig-like touch. Later, Caravaggio brings light as if it were streaming over the viewer’s left shoulder, alighting on the canvas. Now we see, we feel a dual effect: the dark background pushes the figures towards us; the light shining from behind and above us nudges us towards the painting. He is an in-your-face painter.11

6. Caravaggio portrays an intense humanity, a range of emotions in which each character in the drama plays reciprocally against the other, like some small chamber orchestra. Reading and appreciating the feelings of one person — facial, gestural, emblematic (Ekman, 2008) – is best done by studying these in the others of the small drama. None stands alone.

7. There is plasticity from picture to picture of some characters. Within two years, Caravaggio paints two episodes with Christ, showing completely different facial features. It is as if he were humanizing Christ, unlike previous more iconic, standardized portrayals of how a Christ should look. This carries humanization further. In the second Dinner at Emmaus, a beardless, chubby-cheeked Christ appears (three days after being dead) blessing the bread.

8. He uses torso and gesture to insert, insist on dynamism in the moment captured. That is, he recognized that emotion (whose root comes from “motion”) is captured not only in the face, but also in gesture and “movement”. The challenge for the painter, whose creations are static, is how to represent a sense of movement to the viewer. One example is his use of opposing shoulder to opposite hip, baring the midsection, torquing the torso. This is a technique that Michelangelo used, particularly in the Sistine Chapel’s Sybils, and which Michelangelo in turn used from the then recently unearthed Belvedere torso (now in the Vatican).12 Viewers subjectively “feel” this, identify with the “movement.”13

Footnotes

6 I write as an analyst, not an art historian. Many of the painting techniques I mention may have been used by others, but Caravaggio harnesses them to have a more forceful emotional impact on the viewer. For an historical perspective on artistic representation, particularly in the Renaissance, those interested can turn to Barasch (1991). His work is a magisterial overview of the visual representations of mankind from the ancient Greeks through the Renaissance. He articulates patterns of representation of emotion and gesture and the interplay among subjects. One can also read about the representation of emotion in da Vinici’s classic, treatise on Painting (L. da Vinci, 2004)

7 His profuse grey beard obscures the lips’ hints of emotion.

8 Landscape reveals Caravaggio’s technical capacity for greater perspective and three- dimensionality. This emphasizes his infrequent use of perspective; he focuses us on the emotions.

9 The observer may feel the impulse to step forward, into the picture to rescue the falling fruit.

10 Caravaggio, like Michelangelo, appears to have been significantly influenced by the Belvedere torso, a classical torso fragment now in the Vatican museum. When the torso was first unearthed, the Pope asked Michelangelo to add limbs to it. Michelangelo refused, insisting that the statue was too perfect as it was. Instead, Michelangelo used the unique torque of the torso – opposing right shoulder to left hip, thereby amplifying the oblique abdominals and rectus abdominus – as models for his Sybils and other characters in the Sistine Chapel. Such opposing torque (opposing shoulder to opposite hip) is often used by Caravaggio to add dynamic movement to his portraits.

11 In the Scuderie Rome Exhibit the canvas’s attraction of the viewers could be seen over time as they looked. The viewers began from afar, then inched closer, as if some gravitational force were acting. Multiple alarms led guards – who, from their looks of ennui, appeared accustomed to this — to repeatedly ask viewers to stand back.

12 Caravaggio uses the Belvedere in many of his pieces, including some discussed here, such as the Holofernes’ death throes.

13 Recent knowledge about mirror neurons may explain the neurological bases for our felt responses to this art.