2015 January

Character, Personality; Inner Development

The Greeks give us concepts of Character and Personality, fundamental in our current thinking. Character is etched within; we carry it into all facets of life and are recognizable whether we present as father, mother, child, friend, teacher, hero. When we present in fundamentally different ways in different contexts or if our character is too fluid, others find us awry. And character is consistent once established. To change this before analysis’s inventions happened with profound events, such as Joseph’s near fratricide and later false imprisonment in Egypt.

Personality comes from persona, the masks that Greek actors wore to change and portray roles. Men portrayed women; roles changed with the play.

This distinction — evanescence versus consistence — is fundamental to psychoanalysis. Giovacchini has developed Winnicott’s idea of true/false self, suggesting that we all have some aspect of false, or social self. The question for optimal health is that we feel connected within, a tie between social and true self. What is remarkable is how prescient Antique Greek concepts are to these fundamental psychoanalytic concepts.

Interiorization of experiences.

Recall Bible or the Christ tale. Things happen; God speaks; minds change, but it’s not clear what inner life is present, unless we fill in empathically the narrative lacunae. Joseph breaks into tears before his brothers and we recognize his feelings … or think we do — tears of joy after years of absence; or tears of sadness at years lost; or tears of ambivalence — we’re not certain as he nor narrator tells us. Rachel dies at the roadside approaching Jacob’s home and he buries her. But we are not told that he mourns; neither narrator nor he says this, except … he plants a tree. We feel empathically Odysseus’ connection with Telemechus, but the only thoughts expressed are vengeance. Developing the concept of an inner life that is valued, one that both experiences and can express experiences — is a development, is an aesthetic achievement, is an act of culture. We hear elements of this with Dante, his expressed despair alone at the beginning of his journey; his fear at the fourth Circle of Hell; his horror as dead Farinata sits bolt upright in his tomb, accosting Dante. But, we need not wonder about Cordelia’s thoughts as she listens to her sisters’ greasey words slather Lear’s ear: Cordelia turns aside, whispers, “ What shall Cordelia do?/Love, and be silent…..poor Cordelia!/ And yet not so; since, I am sure, my love’s/ More richer than my tongue.”

Relatedness, Family

We have had families from early evolution. But when do we see elements of familial relatedness, connectedness expressed? We hear this in Bible between father and son, some between mother and son (such as when Rachel dying in childbirth names her son “son of my pain,” whom Jacob renames “son of my right hand.”); we hear little of daughters, save for Dinah’s rape. We hear this in Odysseus and Telemechus or Aenius escaping burning Troy with his son by hand and father upon his shoulders. And then we have Lear and Prospero, about whom we have spoken much.

Emotions Within

As psychoanalysts, we assume that emotions are experienced within and that we share universal emotional experiences:# empathy is a key psychoanalytic ingredient. When do we find both elements of this explicitly expressed in Western representations of inner reality? This can be elusive: for, even when not expressed by the text, we the audience will feel as if the character has emotions experienced within. But let us not assume; analysts do better when we don’t assume, when we wait to learn. Prior to emotions research over the past five decades, cultural anthropologists# insisted that emotions were culture-specific. Ekman and colleagues have confirmed Darwin’s hypotheses that emotions have evolved in man and animal, are universal precisely because they have survival value. If we did not have universal emotions, we also could not reach back two millenia and feel ourselves into the lives of early Hebraic shepherds, or Greek warriors and dedicated wives, into the life of a man yearning to be the son of God and too many more I haven’t mentioned. We share at least their feelings; we can empathize.

Journey as Soul-cure

Journeys have a long tradition in Mimesis. Abraham is commanded, “Leave the land of your father,” and he travels a thousand kilometers. Odysseus leaves and returns. Aenius leaves his burning home and is told that he will know his new home when his men eat their plates. Christ wanders the wilderness. The Decameron is a trip of ten days to leave plague-ridden Florence, or the Canterbury Tales pilgrims. But, I suggest that the clearest major account of a voyage with a guide in which the voyager seeks enlightenment and in which he is to learn about living a better life, is Dante’s through Hell. Virgil knows this path too well, including its treachery. He guides by pointing. Dante sees Francesca and Paolo, hovering, lips almost touching, damned to Hell. Dante must see, reflect, draw conclusions and Virgil paces the travel into deeper levels of Hell. Unlike tragedies in which the protagonist may be enlightened but too late, Dante reaches the Heavens, finds his love. His soul is cured. I leave out for now the journey through time, such as the Thousand on One Nights, in which a dedicated and courageous Scheherezade cures a homicidal king with her woven tales. This is for another time.

And an extension of such a journey is autobiography; rather than journeying through others’ lives, one journeys through one’s own with a developmental vector of early life predicting or explaining or influencing later. This genre was created by Rousseau. One can hear psychoanalysis as an oral-aural development of autobiographical genre.#

One last word from Bellow: each good author tries to solve the dilemmas, challenges left by previous authors. Auerbach adds, we expect writers to develop new ways to re-present inner realities. And those inner realities reflect the world they inhabit, influenced by their predecessors’ worlds.

This paper has been a journey, a vast, but not inclusive sweep. It offers a sense of fundamental concepts of humanity that psychoanalysis inherited. With this I pause in the hope that I have whetted your appetites to feast further on our aesthetics. Then, we will understand both the underpinnings of psychoanalysis, and our hearts and our minds.

Lear and his obverse, Prospero

Let’s leap to Shakespeare, that poet whom Harold Bloom said invented the human. Were we to have time for Lear alone, this would be enough. But, let us press ourselves and place King Lear and Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest, aside each other like twinning, flickering stars to learn how one’s gravity affects the other and enlightens ourselves in turn.

Borges suggested that the tragic man is one who realizes he is in the tsunami’s cusp of his own making, realizes he is about to be overtaken, drowned, only too late to change the course of the wave, to change his fate. He is enlightened, but it is an enlightened darkness, blindness, often death. The Greeks’ tragic hero falls from greatness because of some internal flaw, often hubris, overweening pride. The Biblical Job suffers at God’s whim, despite Job’s silvered soul. Lear begins his own tragedy, in part because … he consumes words; a lifetime’s dedication and acts by Cordelia are not enough. He must be licked, slobbered over, slathered with verses. This is geniused irony: this great wordsmith, Shakespeare, seduces us with words, yet would make the fatal flaw of his great King to be his trust of words, the more the better: “Nothing will come of nothing.” A greater irony that the actor Shakespeare diminishes the past actions of the daughters, until the King catalyzes future actions, until he cracks his crown in two and is left with the empty shells, as his Fool put it to him.

But, Bloom announces Shakespeare as the inventor of the human. Is this audacious?

Lear and his characters need no gods. This is a rebirth, a re-naissance, of the Antique Greek concept that man is a self-contained unit, a body connected to soul, a concept reborn in the Renaissance and fundamental to psychoanalysis (Bloom or Auerbach). Lear and his ilk need only themselves to create intense love and hatred. Love is unrecognized until too late (as with Othello or with Ophelia). Hate is barely hidden from our sight, but unseen by the blind Lear. Ambivalence, that cardinal characteristic that Freud described present in our most charged intimacies, is not as present in Lear nor Job, not in Jacob nor Christ, but more clearly so in Hamlet with Ophelia and even more so in the comedies, such as Midsummer Night’s Dream, where men can’t trust their women … or at least trust their judgment about their loves.

Lear’s women — unlike the paler or styilized versions of those in Bible, in New Testament, even the idealized Penelope, nor the beatific Beatrice whose image alone drives on Dante — Lear’s women are powerfully alive, make themselves felt. Attention will be paid. They are articulate (even Cordelia’s sotto voce), act firmly. They are ruthless or faithful. The family dramas of Bible are comparatively skeletal: Jacob deceives and is deceived; young Joseph is naively overweening. His eleven brothers respond monochromatically. Christ has no clear overt family drama; although he constructs his dramatic family of disciples, including both Peter and Judas. Odysseus’ family drama is stark; the yearning son; the dedicated wife, the home-sick Odysseus. Nothing like the deeply layered hates and loves of Lear and company. How can Kent be so dedicated to this tyrannical King; Cordelia more so, even his Fool, who tries to save him, and the mad Edgar, who in his manner saves both his sanity and enlightens the crazed Lear?

Only in his final play does Shakespeare “cure” Lear, transform him into a wise Prospero. This former royalty must create his own kingdom from dross, in an isolated wilderness; masters the monstrous son of a witch, Caliban, liberates and then commands the sprite, Ariel: all, simply all, to create a future for his beloved Miranda daughter. Prospero’s name is ironic: robbed of his material prosperity, he “prospers” by his magic, isolated on a primeval isle. He only truly prospers, we shall see, when he relinquishes his powers, when he betroths his daughter. Again, with “time’s winged chariot” beating an incessant presence at my back, I summarize too abruptly. Lear breaks his heart over his daughter’s corpse; Prospero breaks his magic staff over his love for his daughter, over his desire to become more human. Lear dies in despair; Prospero lives with integrity. When we read these two plays together, we see how Shakespeare takes us from the “blow winds and crack your cheeks, rage…” of Lear’s towering, deteriorating narcissism to the maturity and ego-ideal forgiveness of Prospero who begs us release him from his bands with the help of our gentle hands so that he may truly prosper.

Lear never sees us who watch; Prospero turns to us in humility and begs our release with our breath, our applause. In the four to eight years between writing Lear and Tempest — a not unreasonable interval for psychoanalysis — Shakespeare has transformed the father’s madness. These tales are of fathers and daughters; of inner lives that are driven mostly from within with no need for gods to do good nor evil. Richard III or Edmund remind us: men blame the stars for their ill … but we create our own miseries … or not. The depth of the deeply human is felt here; it is closer to our conceptions of inner life than we have heard thus far.

——-

Notice how much has changed from Antique and Biblical representations of inner realities. Characters change. Inner selves — faults and strengths — rule us. Intimacies — both of love (Cordelia, Prospero) or hate (Edmund, Goneril, Caliban) — are all that is needed to drive the drama of life. Odysseus leaves and returns after two decades unchanged; only Biblical Joseph (and perhaps Moses) of the many Biblical characters show maturation. Borges’s deeply human Christ dies calling forlornly upon his father who has forsaken him, ending with how King David began Psalm 23. Lear too dies, but knows true love; Prospero restrains his retribution and thrives on his humane love. Shakespeare’s last play is a profoundly human and cautiously optimistic creation. When he turns to us, with his final humble words, this alone earns Bloom’s appellation, the invention of the human.

Time insists on a denouement, although with Shakespeare, we are some five hundred years short of the present. How much I have skipped; and how much I miss in the next half millenia. What’s skipped is voluminous. What about romantic love, which becomes part of our canon between the poles of chivalrous Medieval literature versus its comic representations in Boccaccio’s Decameron#? Quixote, a parody of the chivalrous, has within it something closer to romantic love, including his blindness to his broken-down steed Rocinante or pock-faced Dulcinea. Shakespeare hits directly to our hearts of romantic love with Romeo and Juliet. What of women’s voices, initiated by Sappho, and emerging full-throated with Mary Shelley and Virginia Woolf? And Flaubert’s flirtation with pure style to overcome the dross of content in Bovary or his final Bouvard et Pecouchet? Joyce’s attempt to write the novel to end all novels as a genre, with Ulysses, then with the riotous neologisms of Finnegan’s Wake? If there were time, I would end with Bellow’s work, final Ravelstein, a tale of a dedicated friendship-love between two men and ultimately between a man and woman. The voyage of Ravelstein and author has the taste of a Dante-Virgil journey, but one in which both strive for the other to develop wisdom. All these and too much more we will need to leave for the future as I turn now to draw some thoughts of what we as psychoanalysts can learn about the constructions of inner lives that we have inherited from two millenia of aesthetics. What can we conclude?

SLIDE 7: Escher

————-

Bounded Personhood; Body and Soul

The Greeks gave us a concept of bounded personhood (Bloom and Auerbach): that we have a concept of our body and mind somehow connected; that we think of ourselves (from early toddlerhood) as someone who can act upon the world and upon whom the world acts. This differs from a concept of feeling ruled by forces outside ourselves. But even this concept among the Antiques (Greek and Roman) was not entirely formed. The Greeks believed that anxiety — that pounding heart, that shortness of breath — was sent down from the sky and grabbed us by the chest. The Romans believed that seeing was truly physical. Our eyes emit invisible tendrils that feel the object. Or the object sends out tiny particles of its shape that bombard us. The evil eye was a true physical fear (Bartsch). Not until full-throated Renaissance, and particularly with political freedoms, do we have both a recrudescence and development of concepts such as autonomy, and the demand for freedom. And more so, do we have the rise of empiricism and belief in reason. These are part of our psychoanalytic fabric, but we know too well how earlier, more primitive senses of self remain undercurrents in our being: the patients who do not feel connected with their bodies; or whose bodies, they feel, rule them with out psychic trace; those — often not psychoanalytic patients — who feel either the devil made them do it or touched by the grace of God.

The Christ tale:

A man born human, believes himself divine and dies knowing that he is but human (Borges).

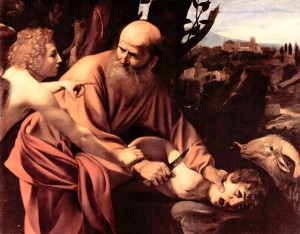

Auerbach picks Peter denying Christ to portray the New Testament’s innovations. I focus on his concept of figura: that the Bible spiritually prefigures the New Testament: Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac becomes complete in God’s sacrifice of Christ; nonagenarian Sarah’s conception is bested by Mary’s immaculate conception. We might call this horizontal figura. I extend this concept vertically: all that happens below on earth is paralleled in heaven. “No sparrow falls from heaven that is not seen by God,” insists Matthew (10:29). Figura is an articulation, a connection between the past to the future, or between what happens in the “below“ of our mind/bodies and our higher consciousness.

Recall the Peter scene. Christ creates his circle gathering fishermen, carpenters and a prostitute. Great things will happen of these lowly characters, extensions of the Old Testament shepherds who make good. But, the Biblical Jacob and Joseph must make their own fortune on earth with no heavenly promise for these fortunes; only faith will count to build a nation. Christ in contrast ascetically disdains earthly delights and leads himself to sacrifice, trumps the foreordained but incomplete near-sacrifice of Isaac. His ascetic denial of the flesh is replaced by search for meaning. Christ follows what he believes are his father’s wishes, sacrifices himself for his followers, a new innovation in narrative, a new worldview: one’s death will improve the world, create a future. This is not Odysseus, nor Jacob nor Joseph. Psychoanalysts can see this retrospectively as a grandiose view of masochistic narcissism,# but let us take the tale as it stands and even ask to what degree it is embedded in our inner lives.

The Peter tale creates the setting for unremitting guilt. Promising Christ he would never deny him, Christ insists he will thrice deny before cock’s crow. Peter hides nearby as Christ is denounced. Peter, suspected because of his Galilean accent and appearance to be a Christ follower, succumbs and denies him. When the cock crows, Peter realizes with remorse that he has fulfilled Christ’s prophecy.

Figura is the architecture of New Testament, the structure of a world view. Christ and his disciples, are plebian. This is a view of how a better world will be built, by plain men, not great heros. Peter’s denial of a man he loves sets the stage for deep-seated guilt that becomes a keel guiding his boat of belief; it is the nave that runs along the spine of the Church. Nothing like this we find in Bible nor Homer. It is an innovation, which, measured by years of endurance and numbers of believers, is a successful foundational myth. Something here has etched deeply into man’s psyche. Yet, there is also some kinship, some continuity with the Greek myth: like many Greek characters, although not Odysseus, Christ is born of the union of a God and woman. A demi-God arises who dies a human, but leaves behind great beliefs and believers. Perhaps this is Christ’s tragic flaw and lesson: we may wish to believe we are born demi-gods, but … if we do not outgrow this, we are doomed, as Borges suggests.

Before we leave this, note that Auerbach contrasts the asceticism of the New Testament with the sensuality of Homer and Antique literature. This reverberation between asceticism and sensuality we find embodied restlessly in Anna Freud’s account of adolescence (Anna Freud).

Through the Circles of Hell: Dante and Virgil

We leap centuries, coming briefly to rest at nodal points when our inner life and worldviews reconfigure. Dante’s Inferno is our next way station, a writer so powerful for Auerbach that he wrote a treatise on him alone before Mimesis. In two papers, I suggest that Dante’s discoveries, his innovations, set the stage for what eventually becomes a psychoanalytic enterprise. Dante begins his poem, written in his mother tongue, a severe choice when Latin was the language of serious art. This poem is by a poet about a poet who in the middle of his life finds himself in a dark wood. He first tries to ascend directly to Paradise, as many men of midlife crisis, but tumbles down into his previous despair.

Alone, despondent, Dante realizes he must navigate the depths of terrifying Hell before he can ascend to his beloved Beatrice in Heaven. Terrified, Dante turns to a hoarse voice, one which has not spoken for centuries; he recognizes his ego ideal, Virgil, poet of reason, that creator of Aeneus, Odysseus’ vanquished counterpart. Virgil offers to guide Dante and structure their journey. The nature of their interactions create a model for soul-healing.

First, Dante understands that the journey must be in levels, the less dangerous preceding the more treacherous. One cannot plunge into the depths of Hell and survive. His guide takes him through Circles. At each Circle, Virgil expects Dante will learn some wisdom about one’s sins and how to avoid them. Their relationship is telling: Virgil points out, waits and permits Dante first to decide if he is ready to see what stands before him, and if ready, then draw his own conclusions. Virgil does not tell him what to think. Contrast the Biblical God, who commands righteously; Christ swho peaks with certitude; Athena, who demands actions, mayhem, in order to proceed. Virgil asks Dante to observe, “Let thy words be numbered” and to reflect. And early on, when Dante hesitates at the Fourth Circle, when Dante looks at Virgil’s paling face and misinterprets this as Virgil’s fear, the poet of reason responds: you see correctly fear in my face, but it is my fear for you not myself. Virgil has trod this path before; he knows the vicissitudes of this journey. This, you hear, this poem comes closest to setting a model of a layered mind, a model of how a dialogue between an experienced and trusted guide, one known for his reason, but knowledgeable about intense feelings, this guide who respects his journeyman, who has ventured this treacherous path before, this is the closest we come to a model for psychoanalysis.

This sixteenth century poem lays out basic ingredients for layers of interpretation and the working relationship that can permit soul healing. And ghosty Virgil is a realist. When Dante wonders why he should proceed, when he questions what motivates Virgil to help, Virgil says in the beginning, that it is because of the love of a dear woman, Beatrice, that Virgil came and it is for that love that Dante must proceed.

Later in the journey, Dante’s discoveries and experiences become enough to motivate him, to move him. And once Virgil has guided Dante safely through Hell, climbed the legs of terrifying Satan, passed through Limbo, at the gates of Paradise, Virgil hands his charge to a woman, beloved Beatrice, who will guide him through Paradise. We have seen nothing like this that prefigures psychoanalysis so sensitively.

Ethiopian Children growing up in Israel: Identit(ies), Relationships, Inner lives in Transition

The next psychoanalytic challenge is to reach across at least three boundaries: two cultures with two languages and the boundary of childhood. I have started a study of Ethiopian Fallash Mura immigrants, who were force-converted to Christianity one century ago, who have immigrated to Israel, and to study their children’s development.

Ironically, as a child therapist, I find children more available, readier to express their inner lives than many adults.

How do these children develop their identities, their emotional lives, coming from a deeply rural, impoverished, highly traditional, hierarchical pre-literate society, then immersed into Israel, a highly-educated society with first-world technology and the associated cultural values? In rural northern Ethiopia, boys of 14 or 15 had their own flocks of goats and were expected to earn their way. Girls of 14 or 15 were engaged or married. Fathers carried much weight. Many of the mothers were tattooed with crosses on their foreheads, cheeks, necks as children, and continued to accumulate tattoos even after emigration and professing Orthodox Judaism. In Israel, life is quickly flipped. Children are in school until 18, then off to the army. Girls are legally not permitted to wed before 17 or 18. All child support from the government is funneled through the mother; many Ethiopian men complain that Israel is a women’s country. Vocations useful in rural Gondar are not feasible here: weaving, blacksmithing and pottery making, goat herding. Children spend much of the day in school, become fluent in Hebrew and become translators for their parents, who are now illiterate in two languages, to paraphrase Berthold Brecht.

The challenges to integration are great. Previous Ethiopian immigrants who had maintained their Jewish identity, still showed greater difficulty both integrating and making progress in Israeli society compared to other immigrant groups: rates of juvenile delinquency, school drop out and drug use are several-fold higher. Ethiopian boys adopt Rastafarian identities. Because of the long waiting period in Gondar, some fathers make aliyah first, leaving wife and children behind. In Gondar, it is culturally acceptable for a woman living alone to be taken-up by any man who chooses to; this is not considered rape in that culture. If she becomes pregnant and gives birth by that man, he and his family expect her to take the child to Israel and send money to support the man in Ethiopia.

In Israel, school class size approaches 40 children.

In light of this, in the ‘90’s Elie Wiesel and his family have established two after school programs in two communities: Ashkelon, a Mediterranean city, and Kiryat Malachi (“City of Angels”), a town in the northern Negev, about ten minutes drive from the better-known Sderot.

In this little city of angels, I began visiting, consulting and have started a study of these children’s development and their relationships. I begin with 5- 6 year olds, knowing that this is the earliest age at which I would have access, and believing from much of our psychoanalytic developmental research, that earlier is better and often predictive of later development (Massie and Szajnberg, 2005, Sroufe, et. al. 2005).

Now, to most scientific audiences, I could say that my “instruments” and measures are the current standards for learning about behavior, inner life, achievement and attachment for these children and their mothers: academic scores, I. Q., Child Behavior Checklist, projective drawings such as Draw=A=Person, House-Tree-Person, Kinetic Family Drawing, the Waters-Deane Q-Sort for attachment and for mothers, the Attachment Projective Test. All this would be true.

But, these would not be as effective if I could not as an analyst, as a child therapist, know how to enter the inner worlds of others, be invited to enter. Good cultural anthropologists know this also: to immerse oneself in a community, to find “informants” who can help cross-cultural boundaries. But, to enter the worlds of children, intriguingly seems easier, as Winnicott showed in his Squiggle game book. The first case in that book was a Finnish boy; of course, Winnicott had a translator to describe what the boy was saying about his drawings; but the boy was engaged by not only the visual drawing-dialogue with Winnicott, but also by Winnicott’s ability as a child therapist to engage the child, to show the child his interest in the boy’s inner life, not for voyeuristic reasons, but for the boy’s sake.

Squiggle game: engaging imaginations; DWW what is child’s purest transference fantasy of analyst.

Here, among analysts, I can say that before I used various “objective” instruments, the major instrument was myself, my training to listen and observe. Going to Beit Tzipora weekly, entering the classrooms, the playground at breaks, helping read or playing, are techniques that come from child therapy, and also from Whyte’s participant observer approach which he pioneered in Street Corner Society in the 1930’s. When, after weeks, the children begin to seek me out, ask me to visit their class, help fix a lacrosse ball, give them airplane rides, or just hold my hand to walk back to the classroom from which a boy had recently left in despair. I become an instrument to learn about the inner worlds of these children, in such a way that they feel connected and in such a way that I might be able to learn something to bring to colleagues. Something about how identity develops in such a great leap across cultures, language and even eras.

What happens within the room, and within me when a child makes a drawing, then tells a story. There descends a quiet, an intense quietude. Something envelopes both me and the child. I ask for a ‘person”, a girl asks, “ Can I make a heart first?” Then, she rests her head on her left arm and begins drawing.

Orna’s story: Family: Micky Mouse and two sisters, 15 and 16. In Hot air balloon. That’s the family; parents died last week. (?) they feel beseder. M M takes care of them; holds the balloons rope, so the sisters won’t fall. Parents were M’s too.

Aviel: (Girl?). Can I draw a war? It’s a dream. Castle with King Saul. David and Goliath. Blood runs down “goliaths nose (he makes a disticnct line with his finger from forehead ot noes tip, as he did when he drew pic of his dog – I ask about this) Yes, the white line on my dog’s noes means he is dangerous. That’s why we put a muzzle. Saul drawn as if standing on Goliath’s head. Next to him is KKing Saul, then Saul dead, with shield at side. As he walks out: he says he is Saul; Saul killed, but after Solomon, no kings are killed, he says smiling.

Rudy Ekstein once said that when he feels stuck working with a child, he has old teachers perched on his shoulders whispering advice into his ear – what to do next, what to say. As I prepred this talk, I thought of only a few teachers who whisper in my ears as I sit with these children. Bob Levine, the anthropologist taught me about having local informants who know not only the language, but also the gestures, the customs. Bruno Bettelheim, who taught me too many things to summarize, but in this case, being transported into the inner life of the child. Sally Provence, who taught me not only developmental assessment, but particularly bringing out the best performance in a child. Barry Brazelton, who like an orchestra conductor, brings a baby to life, shows even the baby how competent it is, how active the baby is in connecting, coming alive with the world.

After Lives Across Time, my next study was to be of transition to young adulthood among elite Israeli citizen soldiers. I designed this study during Oslo, after Ehud Barak announced that he would decrease the size of the army and the length of service. Also, the kibbutz as an institution was changing, even disappearing; I thought this would be the last opportunity to study its offspring. I designed a study using semi-structured interviews, similar to our US study, looking at 20 men and 20 women raised on kibbutz or moshav.

My first trip to Israel was in Oct 2000, the outbreak of the second Intifada. The first International Conference on Infancy was to be held in Israel; it was cancelled. I went to Israel. I chose to spend the two weeks working in a kibbutz persimmon orchard and begin interviewing soldiers.

My women soldiers kept telling me that I should be talking with their husbands, brothers, and boyfriends. The women enjoyed their two years service, found it fulfilling; but they insisted, I needed to listen to their young men. After several such spontaneous remarks, I changed the study to that of these young men.

Further, during an Intifada, I could not ask these fellows to sit in an office to be videotaped and interviewed for 3-4 hours. They had enough to do without this. And, they wanted to meet with me, interview me; wondered what the heck this American was doing in Israel when the tourists had evaporated. Two prestigious visiting Professorships at Ben Gurion University were unfilled for several years, as invited guests were too afraid to come. Interviews I scheduled were missed because a soldier was called up to reserve duty and in one case, had been wounded in action. In the latter case, when his wife heard that I was on the bus in Samaria traveling to the kibbutz, she invited me for tea and to talk while her husband was in the hospital.

My semi-structured interviews waited and waited. I would have multiple meetings with these fellows, generally over several months, in cafes, or on midnight Jeep security rounds on kibbutz, or in the guardhouse, or in the security station near Jenin, or for 3 1⁄2 hour walk after midnight just before a soldier was to return to duty. Then, I could sit, tape an interview. And afterwards, almost all the soldiers wanted to stay in touch; remembering something significant that they thought I needed to know about childhood; or birth of a child; or to meet the fiancé.

I made twenty-four trips over the next four years.

Here, being an analyst, listening as an analyst, facilitates working across cultures. Bob Bergman (In Szajnberg, 1994) wrote about how being a psychoanalyst and having worked with institutionalized children at the Orthogenic School, taught him to listen better as a physician and later a shaman among the Navajo. One learns about the aesthetic structure of conversation — pace, pause, silence, affective tone — and social signaling described by Erving Goffman — the body posture, the gesture, the gaze and gaze aversion — the signals that can be highly culture-specific and which often arise with affectively-laden subjects, such as talking about one’s inner life. I also turned to my friend and colleague, Paul Eman’s work on facial expression of emotion (and gestural expression). I began to notice how much I attended to face and to body gesture to time my responses (Ekman, 205).

That is, taking a word such as “empathy,” we can begin to parse, explore how it works in technique. Without some consensus on empathy’s nature, one person’s “empathy,” can be another’s intrusiveness, or another’s aloofness. An example of the effect of culture frame of reference comes from anthropology. When Ruth Benedict studied the Navajo, she described them as a quiet people; when decades later a Japanese anthropologist visited, he was struck by the Navajo’s noisiness. To some degree, we could say that a measure of an empathic remark or inquiry is the response (by analysand or research subject): does the person open to richer, more enlightening matters. This is after the fact, the interpretaion or inquiry.

But, how can we judge an interpretation or inquiry or comment on its face, before the person’s response. In the consulting room, how do we weigh what we are about to say, or not say? We can start with Freud’s criteria for a good interpretation: solid content, timing and affect. But, just as Leonard Bernstein articulated five criteria for judging the quality of a musical composition, he added a sixth: does it hit the heart. Therefore, my effectiveness of moving into a culture, of moving into the inner lives of my soldiers, or children, can be assessed by their responses and the reader’s sense of whether something new, enlightening, meaningful is opened. In turn, if you find that these soldiers accounts of their lives is moving and perhaps enlightening, we can look at the techniques for inquiry – techniques that were formed by psychoanalytic work. (Give e.g. of Dud’s interview)

Therefore, when I say that I interviewed Israeli soldiers, I cannot only tell you about the AAI, the anamnesis, and the phenomenology of symptoms. I must also tell you about our psychoanalytic stance of a peculiar listening and speaking and the capacity to maintain a certain empathic neutrality that differentiates us from others — journalists or memoirists, for instance. In addition, like Bob Bergman, working with children — work that involves more action, play, even withstanding aggression– also permits an ability to balance observing with experiencing ego. As analysts, we not only tap our observing egos, but try to facilitate this in the speaker: I found that encouraging the soldier’s self-reflection not only taught me more about my soldiers, but also, brought a sense of self-enlightenment and sincere engagement in our collaborative work. They wanted to talk more, think more, understand more about their lives.

Yet, even this is not a full account of my methodology. You will gather that the soldiers noticed that I was visiting Israel when others were not; that I would meet with them in cafes, kibbutz guard houses at midnight; make Jeep tours of the electrified fence after midnight; travel to their kibbutz in Samaria or their reserve guard duty at the outskirts of Palestinian Jenin. That is, as in child work and even psychoanalytic work, I had to demonstrate that I could enter their worlds, at least to visit. For the psychoanalyst, the counterpart or the complement to a transference neurosis is our willingness to enter at least briefly, at least partially the frightening or the dangerous in the inner worlds of our analysands, and to do so “armed” only with our knowledge and a kind of restrained passion. This willingness, I used to be among these soldiers (Flarsheim, in Giovacchini, 1984)

These soldiers asked questions. Why would I visit, when others don’t, for instance; why am I doing this study. I could answer some questions directly. But other questions I had to defer, such as “What do you think of Jews living in Samaria (or the West Bank)? What have you learned about soldiers?” Here, my honest answer was that I needed to learn more from them, from their fellow soldiers. These soldiers came with a spectrum of political beliefs. In order to sustain dialogue, I kept my political opinions to myself. Nevertheless, when a soldier living in a kibbutz in Judah, asked time to visit him, I did so. This may seem self-evident to those here. But, I also had a close friend, a left-wing supporter of Yossi Beilin, a kibbutznik, who as a matter of ideology, refused to set foot in the “Territories.” This I could not afford to do if I were to hear stories from as many soldiers as possible. My friend’s principles were political; my principle was to learn about transition to young adulthood an inner lives of soldiers; psychoanalytic study is central; politics, I put aside.

Freud cautioned the analyst, be prepared to be surprised.

And, I was prepared to be surprised. I knew I would have information about their early development, about entering the army, peak experiences in the army, in battle, about life afterwards, about attachment. But, on listening again and again to the interviews, reading my notes, I discovered something new about courage that led me to re-read Aristotle’s work and others and to present this to the Chicago Psychoanalytic, with the privilege of a discussion by Jim Fish, whose two sons and now one grandson serve in elite combat units in Israel. Again, this is not the time to tell you about all I learned. But, I can say that these boys had a more demanding definition of courage than I. What I considered courageous on their parts, they dismissed, not only out of their modesty, but also because many of their acts were done out of repeated demanding training. They considered courageous those actions that went beyond training, and always were acts by others, not themselves. I will tell you about Nehemiah Dagan for instance, a now-70-year old former helicopter pilot, who started the helicopter attack force in Israel. (recount saving of downed pilot in Egypt). While he is reluctant to recount this tale, he talks with deep feeling about his son’s courage when he flew the first planes throughout the night to rescue the first group of Ethiopian Jews encamped at the desolate border of Sudan and Ethiopia. This, he insisted, was true courage.

Listening as an analyst includes knowing when not to speak and when speaking, to use Freud’s three criteria for interpretation: what is said, how, and when.

When I speak about these boys, I tell the stories of Dudu, Amit and David below. But their full stories need to be told, not simply read.

(Story of Dudu: realization that he lives three, not two lives, including life of father’s buddy, Dudu.

Riding in night jeep patrol on kibbutz; speaker becoming so involved, he looks at me as drives.

After midnight walk with David, to hear about buddy getting raked by machine gun fire and saving his life. He swivels about hearing someone behind us walking, reaches for gun in small of back and explains he leaves them at home because of this.)

Our thirty-year study was the follow-up of Brody’s cohort from 1964. In a sense we were performing an archeological dig, in which layers are often up-ended, folded around, seeking fragments, forme fruste images. Then we try to reconstruct the life history of three decades from the images we discover. In a sense, we are getting a snapshot of a character built over many years. In a sense, we are making a movie backwards. We are matching-up what is revealed to us today with what we discover in archives of observations.

We study memories.

For this, we had archival observations, which we reviewed after we completed our interviews and assessments of our 76 subjects. We chose to assess current life in several ways. First, we used the Adult Attachment Interview. Not only does this assess attachment, but it also gives us a sense of significant events in the person’s life and how their memories work. We also used semi-structure interview to assess defensive style, Erikson’s developmental level and phenomenological psychiatric status. In a sense, as analysts, the AAI was our most valuable glimpse into inner life. One asks: tell me five words to describe your mother’s relationship with you as a child; then, give me a specific memory for each word. This is deeply revealing. For instance, Fonagy has written about how one can use aspects of the AAI scoring to assess reflective capacity.

We matched how people remembered against the prospective data, finding that in general there was remarkably accurate memory for significant events and occasionally, we learned that the person’s affective memory clarified a previous research observer’s assessment; and in some instances, memory was judged far more accurate than researchers’ previous knowledge. For instance, at 6 years of age, a researcher sees that a father has been building a Heath kit project with his son; the researcher is deeply impressed with the project and believes it reflects that father’s connection with the boy. At thirty, this former child spontaneously reports that the Heath kit project was inordinately boring and reflected how this father had projects and ideas not connected with the boy’s interests.

An example of how the thirty-year old reveals a remarkable event missed by the researchers is of a mother’s recurrent psychotic depressions and suicide. When this child was seven, she refused to meet with the researchers for her annual assessment, until the headmaster insisted the child comply. The child reported that mother was vacationing in one of the family’s multiple homes – Mont Blanc or Montserrat. In fact, the mother was “vacationing” at a private psychiatric facility for eight months, where the child visited weekly. The young man was then interviewed at eighteen, reporting nothing new about his mother, who, in fact, was then institutionalized again and committed suicide within months of the interview. The thirty-year-old admitted openly that she knew she was hiding this from the researchers. I found similar capacity to hide major events as Medical Director of the Family Mosaic Program in San Francisco, a Robert Wood Johnson funded program for the 200 most disturbed children in SF. Our social workers – who were of the communities — went into the homes, the schools, the streets to find the children and the parents (many mothers were prostitutes; most fathers were in Pelican Bay for felonies). On Portrero Hill, we could find our pre-teen kids skipping school to sell drugs on the street corner, the dealers knowing that these kids would get off easy as juveniles. Yet, repeatedly we were impressed with how the extended family and the community were able to hoodwink our dedicated workers, often to the detriment of the children.

I won’t try to repeat our findings here, which we published in several articles in IJP and will be republished by Karnac as Lives Across Time. My focus is on how to learn about how inner lives are constructed and how memory works, including how memory as an ego function can be distorted when ego structure is badly affected, and how basic memories are accurate with some severe ego defects — how one man with a GAF score in the 70’s clearly recalls the dismal details of his very difficult childhood. His art work had the quality of late Arshile Gorky – an apocalyptic, dark, nature of destruction. We believe that our work can contribute to understanding how memory is constructed.

A note here about the analyst’s reaction to listening and watching these interviews. One of our innovations was to establish a likeability measure. We developed a Likert-type instrument, asking,”To what degree do I find this person believable, sincere, accurate? How much would I like to listen to this interview again?”

Szajnberg, NY Jan 2007

I have two related goals today. First to describe four different psychoanalytic studies and the challenge of finding ways – methods – to learn about our “subject” — our inner life – when our primary instrument to study this is – our inner life. Second, if we have time, I want to encourage our thinking about our psychoanalytic community as a community of scholars by looking at previous communities of inquiry.

Art Nielsen asked me to present some of my research to discuss the challenge of seeking proper ways to investigate inner life from a psychoanalytic perspective. I will present four studies: two I have completed – one on child development, the second on Israeli soldiers; two in process – a study of immigrant Ethiopian children, the second of character structure and change in psychoanalysis.

A major challenge to psychoanalytic investigation is a constraining social science model of how research should be done: observable matters that can be measured in a statistical manner. Engraved in stone on the face of the Social Science Building at the University of Chicago is a quote from Lord Kelvin, the chemist – I paraphrase — “If it can’t be measured, it can’t be proven.” A Chicago faculty member seeing this commented sarcastically, “If it can’t be measured, do it anyhow.”

Some problems with statistics may be solved with improved statistical methods, such as Guttman’s Partial Order Scalogram Analysis or Small Space Analysis. But, this solves only some problems. A fundamental problem or challenge is the nature of our subject – inner life – and our primary instrument – our inner life. When self-psychologists state that empathy is the major method of cure, how do we “measure” that? It approaches an aesthetic judgment in art. Let me turn to the four studies, focusing not on the results, primarily, but on how we learned about our subjects.

Ethiopian Children growing up in Israel: Identit(ies), Relationships, Inner lives in Transition:

Time presses us to move to Odysseus and Telemachus before we alight on the next father-son pair, God and Christ.

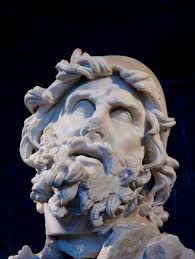

Odysseus, Auerbach summarizes, is a great man, a warrior; Homer deigns to write only of great characters. The Antique Greeks wrote in two different styles: high for great characters; low for the hoi palloi (Auerbach). For the Greeks, character is etched (as the word translates), engraved in our bones so that we are recognized wherever we turn.# Both character (eidos) and persona are words of Greek origin: persona is the mask that actors wear to portray different roles; character is what remains consistent in all settings. Just as each letter is a character to distinguish it clearly from another, so too, man. (This distinction between persona and character may be a vorspeisse of false social self versus true self.) Odysseus is cunning, crafty from beginning to end. Remarkably, Auerbach says, Odysseus over two decades’ voyage does not change. He leaves his one month son, Telemachus and his dedicated Penelope, who fends off suitors/squatters. After twenty years, let’s turn to Odysseus’ disguised return to meet his son Telemachus.

First, as if to prepare us, we hear of Odysseus meeting Eumaeus, his trusty, dedicated swineherd who does not recognize the Athena-altered old man. How does this representation of reality differ from Bible? Listen to the details of Eumaeus’s cottage and swine styes:

...built by himself… with stones from the quarry.. and coped it with a fence of white thorn and he had split an oak to the dark core and…driven stakes the whole length thereof.. and within the courtyard he made twelve styes hard by one another to be beds for the swine and in each stye, fifty grovelling swine.. but the boars slept outside.” (Book XVI).

How visual; how sensual, how different than Bible.

Then, father sees son, who doesn’t recognize him. Even after Odysseus says, “I am your father, for whose sake you suffered many pains and groans and were submitted to men’s spite,” even after he kisses him and sheds a single tear, Telemachus believes some god deceives him. Finally, he flings himself on father’s neck and “…they wailed aloud, more carelessly than birds, sea-eagles or vultures of crooked claws whose fledgling young the country folk have taken from the nest…” They would have cried all night, Homer tells us, but Odysseus gets to the matter at hand: massacre Penelope’s suitors. Athena insists Odysseus must first make blood before he can make love. This goddess has priorities.

The next episode tells us more of Odysseus character. Again, too briefly, Odysseus, disguised as a beggar enters his old home. Unwitting Penelope greets him and asks Euryklea, his former nursemaid, to wash this stranger’s feet. Odysseus, realizes that Euryklea will recognize the scar on his thigh; he claps one hand on her mouth, the other on her throat and whispers roughly, reveal my identity, and I will throttle you. A decisive man, even ruthless.

Auerbach places these texts side-by-side to understand their Weltanschauungen. The Bible’s narrative is spare, we see the moment, foreground; we know little of what characters think or surrounds them. All is shot with a shallow lens. Abraham takes Isaac hiking three days to sacrifice him; no word is spoken until the foot of the mountain. Jacob calls Joseph to send on a lengthy journey; Joseph answers Hineini, that fateful, single Biblical word, “Here I am,” a word that portends something unknown, powerful and likely dangerous. One God they possess; a God both feared and yet turned to for protection … or at least justice. Intimacies are charged: Joseph’s brothers hate him unto death; Jacob adores him; his mother is dead. Family, a people-to-be, possibly a nation, is foremost in Jacob’s and Joseph’s minds. Jacob’s women — four — clamber upon him; for Joseph, one is briefly mentioned. Names carry meaning: Jacob — either “ankle-grabber” or “crooked one.” Joseph, “and God will add (another son).”

Homer’s characters are voluble. What they think, they tell; where they are, Homer says. How did Odysseus get scarred some forty years earlier? Odysseus/Homer flashes back, his hand hard upon Euryklea’s throat. And Homer speaks of great characters, no rifraff rabble, no vulgus here: we hear of gods or demi-gods, not shepherds or tent dwellers. Names carry meaning: “Odysseus” is “one who is wrathful/hated”; “Telemachus,” “far from battle.” Odysseus is admired for his cunning and deceit. And Gods — battling, petty, impregnating, form-shifting — reign Odysseus’ life, with one his guardian, a beautiful goddess of war. Intimacies are limited: all Odysseus’ men die; he yearns for his dedicated wife, but is “fooled” by bewitching Calypso, stays with her seven years, believing that it is but seven days, a (self-) deception clever Odysseus would like his listeners to believe.

In both texts, names carry meaning. Names condense. They concentrate “unconscious ideas and images of self hood,”# place in family and identities. These identities are imposed upon us and often accepted or rejected, such as in Moby Dick’s protagonist, who begins, “Call me Ishmael.” We never learn his given name; only that his assumed name is of a son sent out by his father to die; instead, this young man, survives as he searches for an identity. But, Joseph ultimately becomes his name: while he was named “to add” pointing to his brother to come; in adulthood he adds to, enriches the lives of others.

“Begin at the Beginning and end…”

“The End is in the Beginning”

Let us begin with Bible and Homer, with a meeting of father and son. Auerbach compares the Abraham-Isaac Akeda, the binding, to Odysseus meeting Telemechus after two decades absence. Here, I compare the Jacob-Joseph meeting after two decades with Odysseus-Telemechus and the relatedness between the father and son. I suggest several reasons to select Jacob and Joseph rather than the more notorious Abraham – Isaac story.# I suggest that the Jacob-Joseph story is the foundational myth of father-son relatedness that permitted an enduring Judaism. Further, we know so little about Isaac; he falls silent after his near sacrifice; speaks only until after his father’s (and mother’s) death.#

Of Jacob and Joseph we know more than earlier Biblical characters, a lot for the laconic Bible, a book that Auerbach says — unlike the Iliad and Odyssey — gives little background, much foreground and hence presses for hermeneutic interpretation. Homer and his characters are voluble, tell us what they think, flash back into histories. Of Bible, we have a desert of description, succinctness of acts or words, descriptive aridity. Following Auerbach, after we touch on Bible, we turn to Homer.

The father Jacob is notorious. Battling his twin in the womb, later described as a tent dweller unlike his hunter brother, he soon bests his brother, plots against his father with mother’s collusion and is on the lam from his brother for two decades. His name, “Jacob” is a pointing name: “heel grabber,” as it points to his brother who preceded him in birth. Later, deceived by his uncle/father-in-law, whom he deceives in return, Jacob escapes home with two wives, two concubines, twelve sons and a daughter and wealth. After battling God’s angel, he is renamed Yisrael# — “God-battler” — he goes through other travails including losing his favored son, Joseph (unbeknownst to Jacob, because of his envious sons).

Slide 3: Joseph

Joseph’s name also points, but to the future: “God will add,” his beloved brother, Benjamin, their mother dying in childbirth. The favored Joseph proudly (or naively) announces his dreams of succession, of rule, unaware of the envy he generates in his brothers, although his father reproves him after misinterpreting the second dream. Father misses the wish embedded in the dream: that Joseph dreams his mother alive. Joseph, sent by his father to spy on his brothers’ industriousness, is cast by them into a pit while they plan his murder, then is saved by one brother, who sells him into slavery (to the offspring of Ishmael, Abraham’s exiled son). I course through this rapidly. But from Joseph’s descent into the pit and his later Egyptian pit-imprisonment, emerges a different man. This reborn Joseph shows evidence of an ego ideal, the first such evidence of this psychic structure in the Bible. I refer to the more creative , super ego-softening aspects of the ego ideal (Chassguet-Smirgel and later Giovacchini), the agency that works for Freud’s object “loved rather than dread(ed).”(Laplanche and Pontalis, p. 145).

Here are the details in brief. Joseph enriches Pharoah, becomes vizier, then meets his brothers who come to beg for food and don’t recognize him. Joseph breaks into a crescendo of crying episodes. His fifth outburst, as he reveals himself, is heard throughout the Egyptian court. Then a final unabashed sobbing breakdown when he meets his father, Jacob, after twenty years: he collapses on his father’s shoulders. Jacob’s response? “Now that I have seen your face, I can go to my grave.” When Jacob dies, his brothers expect Joseph’s retribution for how they wronged him. Instead, Joseph insists that he will provide for them and their children and children’s children. The brothers expect that Joseph’s psychic structure restrains retaliative aggression only out of father-fear; instead, Joseph shows internalized controls, which are not only superego, but also ego ideal. Ironically, even poetically, Joseph “fulfills” his first dream of his brothers as sheaves of wheat bowing to his sheaf, but with a reversal: he “feeds” those circling him.

In short, a father, Jacob, is promised a nation. But, his son, Joseph, fulfills this dream; a son who curbs his impulses,# won’t deceive, won’t retaliate: one who shows a new psychic structure. The son is not murderous towards his father (unlike Oedipus), nor is this father murderous towards the son# (unlike Abraham or Laius … or Christ’s God); Jacob shows no ambivalence about his son’s successes. Most significantly, Joseph changes internally. He is the first Biblical figure who does not speak with God; yet he accepts a unitary god, which psychoanalysts might consider as accepting an integrated self, rather than the multiple gods who run rampant in Greek myth (or multiple part-objects or unintegrated impulses in our inner lives). See how this contrasts with Odysseus. Unlike Abraham-Isaac or Laius-Oedipus, the Jacob-Joseph pair is a more solid foundation upon which to build an enduring society: one in which a father’s dreams can be realized by his son without murderousness nor envy nor ambivalence on either party. We might consider a Joseph-complex rather than Oedipal as a model to explain part of Judaism’s endurance.